|

How I Learned About Timing Belts

Wheelchairs, Timing Belts and Engineering

My introduction to timing belts began with a senior year Creative Engineering project at Villanova University. The specific project was to develop a stair-climbing wheelchair. My introduction to timing belts began with a senior year Creative Engineering project at Villanova University. The specific project was to develop a stair-climbing wheelchair.

This was a continuing project on which several student groups had been assigned in prior years. The other student assignments had never gotten beyond the drawing board stage.

My good friend, Mike Stevenson (1943-92), and I partnered on this assigned project. Both of us were Mechanical Engineering majors. We came up with a new user-powered design, where the wheel of the chair transmitted power through a worm drive so the chair wouldn't reverse and run down the stairs if the user let go of the wheel (worm drives provide one-way power transmission). Our design left the tracks in the 'up' position for normal chair operation; they would pivot down below the chair's wheels for stair-climbing duties.

Our professor, George H. Auth, looked over our new design and said, "Looks good. Now, build it." But we had no money and the school offered no funding, so he encouraged us to go out and "beg" for components.

Mike and I actually drove to Ohio in a winter snowstorm (in his '62 Ford Galaxie convertible) to visit the chief engineer at American Wheelchair Co. He thought the stair-climbing idea was "a little nuts" but donated a wheelchair to the cause anyway. What a trip. It was so cold that the door locks on the car froze. I remember trying to hold the passenger door closed while Mike drove like a maniac to be on time for our appointment at American Wheelchair.

Our design called for a retractable tracked belt drive. After some research, we decided to use a commercially-available timing belt turned inside out so that the teeth faced outward and functioned like a tank tread. Our design used three flat-surfaced pulleys per side plus one toothed drive pulley hooked to the worm gear.

In those days, Uniroyal was the largest producer of timing belts. Its manufacturing plant and engineering facilities were located in Northeast Philadelphia - about a fifteen-minute drive from my home. I made an appointment and met with Engineering Manager Lloyd Spalter. This personable and enthusiastic guy not only gave me two timing belts and matching pulleys for the wheelchair project but offered me a job as well. Eventually, I accepted and my first post-college employment was as a timing belt development engineer at Uniroyal. (Lloyd was soon promoted to another division and eventually became president of Uniroyal's Consumer Products Division (U.S. Keds), president of Uniroyal Canada and executive VP of Operations. He died in 2013 at age 78.)

Creative Engineering was an elective and an addition to my already heavy engineering class load. Mike and I spent a lot of time on the wheelchair project and eventually produced a non-functional full-size mock-up of our idea backed with detailed drawings for a production version. Time and money constraints kept us from getting the remainder of the needed components to produce a working model.

During our presentation to Professor Auth, we pointed out that we had made substantially more progress than any of the prior student teams. George Auth was a "hard marker" and only awarded us with a 'B' grade, despite our valiant efforts. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that we did a great job procuring important components to construct the mock-up and said that "our ability to scrounge, make-do and sell a concept to businesses would serve us well in our real-world engineering careers." I took that as a genuine compliment since Auth had worked in the engineering world prior to teaching and still maintained a thriving consulting practice.

In 2020 - 55 years after our project, a group of Swiss students have made the tracked stair-climing wheelchair a reality.

The Tacony section of Northeast Philadelphia combined a working-class neighborhood with various manufacturers. One such manufacturer was L. H. Gilmer Company which settled in the area in the early part of the 20th Century and made rubber, fabric and composite items, especially belts and belting. Gilmer was large enough to have its own research and engineering department, headed by Richard Y. Case.

A prolific inventor, Case generated dozens of patents between the 1930s and early '60s. He was awarded the Franklin Institute's Edward Longstreth Medal of Merit for scientific innovation in 1955. In the 1940s, Dick Case invented the modern, synchronous rubber-toothed timing belt. The belt featured molded-in trapezoidal teeth to engage matching grooves on toothed pulleys to ensure accuracy and eliminate belt slippage. Its first commercial application was for Singer sewing machines, replacing a belt made from woven fabric with crude, bent wire "teeth."

Heavy-duty timing belts are still employed to power top-mounted engine superchargers on blown hot rods and dragsters. The Gilmer name is still used by car enthusiasts as well as by RC car hobbyists, whose machines often use miniature timing belts for power transmission. However, the L. H. Gilmer Company became a wholly-owned subsidiary of U.S. Rubber Co. in 1940. U.S. Rubber changed its name to Uniroyal in 1961.

When I began working at Uniroyal in mid-1965, I got to meet Dick Case. He autographed a copy of his book, 'Timing Belt Drive Engineering Handbook', for me in somewhat shaky script. I still have it. Case was not quite 60 when I first met him but he looked much older, had trouble getting around and used a cane. I'm not sure he still drove; his wife picked him up every day after lunch in a newish Cadillac four-door hardtop. Dick Case died in late 1970, just after he turned 65. I guess the hard-charging rubber biz and all its fumes wore him out.

As a new engineer, my first assignments involved making and testing specialty variations of stock timing belts for large volume customers. At the time, IBM was probably the largest user of timing belts, for its popular electric typewriters and its computer punchcard sorting machines. In addition to timing belts, Uniroyal made industrial V-belts, automotive fan belts, agricultural flat belts, flexible couplings and other power transmission products.

The big news at the time was that the soon-to-be-introduced 1966 Pontiac Tempest was to be powered by an overhead-cam (OHC) six-cylinder engine and the cam was driven by a Uniroyal timing belt, rather than the usual chain drive. In late 1965, the Tacony plant got a white 1966 Pontiac Tempest LeMans Sprint two-door hardtop with a four-speed manual transmission. With a four-barrel carb engine making 207 horsepower, it was often referred to as the "poor man's GTO."

|

|

| Pontiac introduced the OHC 6 in two flavors for 1966: a base engine with a one-barrel carburetor that developed 165 horsepower at 4700 rpm, and a sportier version with a 10.5:1 compression ratio, a high-lift cam, a split exhaust manifold, and GM's new four-barrel Quadrajet carburetor. On premium fuel, it was rated at 207 hp at 5200 rpm and was said to be good for up to 6500 rpm. The base engine was standard in the Tempest and LeMans series, while the high-output version was marketed in Sprint editions of the Tempest and, starting in mid-1967, the Firebird, with special badging and performance equipment.

The OHC 6 got a bump in displacement to 250 cubic inches for 1968, but then disappeared from the Pontiac lineup after '69, replaced by a plain-vanilla Chevy pushrod 6.

|

The Sprint could do 0-60 in under 9 seconds. Claimed top speed was 115 mph. I had a chance to drive it up the NJ Turnpike to Uniroyal's research facility located in northern New Jersey and was quite impressed, even though my daily driver at the time was a Corvette Sting Ray.

In those days, Uniroyal held all of the patents on the timing belt; made their belts from the finest rubber (prime-grade neoprene), fabric (neoprene impregnated, high-denier nylon) and tensile cord (high-strength, braided, coated fiberglass - precision-wound and preloaded for tension on a mandrel) and charged whatever-the-hell they wanted. I think they priced the Pontiac belt at $1.76. In comparison, GM paid less than 20¢ for some sizes of fan belts because there were many hungry competitors. Uniroyal's 1960s-era automotive-grade timing belts were so well-made that they could go over one-million miles without breaking; in fact, the pulleys failed before the belt did.

I enjoyed my co-workers and most of my bosses. Bob Wetzel (1939-92) and Joe Reuter (1935-2015) were great supervisors and good mentors, too. Both were engineers: Bob was a Mechanical Engineer, like me; Joe was a Textile Engineer. I learned a lot of lessons about real-world engineering practices during my time at Uniroyal. But working conditions at the Tacony facility were pretty dismal: no individual offices, no air conditioning and office furniture which required daily scrubbing to remove the overnight carbon black "dew" from horizontal surfaces (almost everyone kept a can of Comet Cleanser in their desk drawers).

Uniroyal was a blood-from-a-stone kind of place; pay raises were infrequent and uncompetitive. By August 1966, my search for greener pastures culminated in a new job at Rohm & Haas' Plastics Engineering Laboratory in Bristol, PA. I got a raise of almost 20% and R&H offered better fringe benefits, too. As well as an air-conditioned office. Based on my positive comments and recommendations, two Uniroyal employees jumped ship and joined me at the Rohm & Haas' PEL, Dave Chow and Bob Brudzinski.

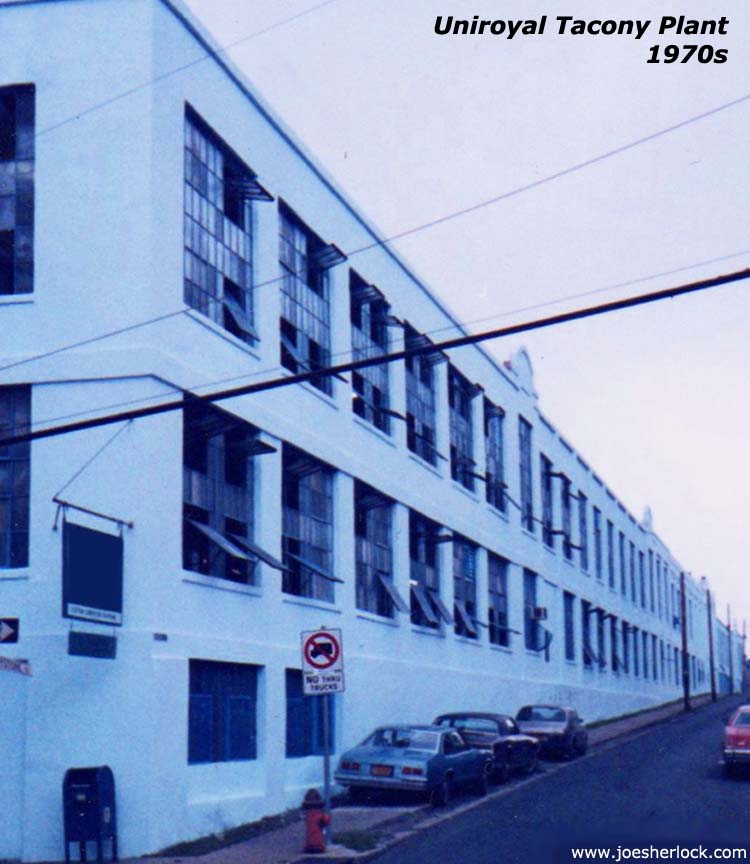

In 1975, Uniroyal closed its Tacony facility, laying off 400 workers and moved the operation to Moncks Corner, South Carolina. Uniroyal's Power Transmission Division was purchased and absorbed by Gates Rubber Company in 1986. Gates is now the largest global manufacturer of timing belts with a U.S. manufacturing facility in Siloam Springs, Arkansas.

Part of the 1923 Gilmer/U.S. Rubber/Uniroyal factory complex at Keystone Street and Cotman Avenue was converted to the Keystone Lofts Apartments in the late 1980s. In 2019, the N.E. Philly apartment building was sold to an Israeli investor for $7.9 million. I wonder if the tenants have to use a lot of Comet Cleanser. And, do the Lofts have elevator service or are disabled residents in search of a stair-climbing wheelchair? (posted 9/16/16, last update: 11/12/20)

Other Pages Of Interest

| blog: 'The View Through The Windshield' |

| greatest hits: index of essays & articles | blog archives | '39 Plymouth |

| model train layout | about me | about the blog | e-mail |

copyright 2016-20 - Joseph M. Sherlock - All applicable rights reserved

Disclaimer

The facts presented on this website are based on my best guesses and my substantially faulty geezer memory. The opinions expressed herein are strictly those of the author and are protected by the U.S. Constitution. Probably.

Spelling, punctuation and syntax errors are cheerfully repaired when I find them; grudgingly fixed when you do.

If I have slandered any brands of automobiles, either expressly or inadvertently, they're most likely crap cars and deserve it. Automobile manufacturers should be aware that they always have the option of trying to change my mind by providing me with vehicles to test drive.

If I have slandered any people or corporations, either expressly or inadvertently, they should buy me strong drinks (and an expensive meal) and try to prove to me that they're not the jerks I've portrayed them to be. If you're buying, I'm willing to listen.

Don't be shy - try a bribe. It might help.

|